Upcoming Dupont Circle (and other) house/walking tours, also an opportunity to consider DC historic preservation issues

- The Dupont Circle House Tour is Sunday, October 15 from 12 - 5 pm – celebrating its 50th House Tour, highlighting the Avenue of the Presidents: 16th Street NW. Tour goers will explore the corridor’s varied architectural buildings ranging from four-story row houses to apartment buildings, Embassies, institutional buildings, and churches.

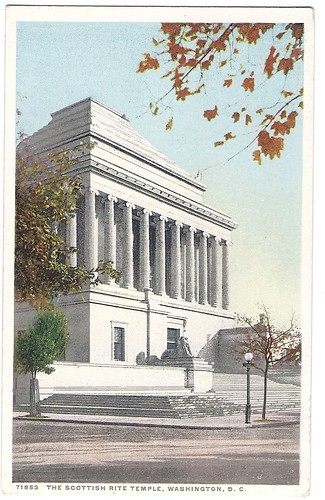

Included in the tour is an afternoon tea at the Temple of the Scottish Rite. Designed by John Russell Pope (who also designed the National Archives and the Jefferson Memorial), the temple was constructed between 1911 and 1915, and was modeled after the tomb of King Mausolus at Halicarnassus. Tickets are $40 in advance; $50 at the door, and may be purchased online. Tickets on the day of the tour are available at the Temple of the Scottish Rite, 1730 16th Street, NW, from 11:00 am – 3:00 pm.

Included in the tour is an afternoon tea at the Temple of the Scottish Rite. Designed by John Russell Pope (who also designed the National Archives and the Jefferson Memorial), the temple was constructed between 1911 and 1915, and was modeled after the tomb of King Mausolus at Halicarnassus. Tickets are $40 in advance; $50 at the door, and may be purchased online. Tickets on the day of the tour are available at the Temple of the Scottish Rite, 1730 16th Street, NW, from 11:00 am – 3:00 pm.

- On Saturday October 28th, design buffs can join the Historic Bloomingdale: Victorian Secrets Modern Truths House Tour, which celebrates this hip, fast-changing neighborhood in Northwest DC. The event includes self-guided tours of eight to 10 notable Bloomingdale residences; a lecture by architect Ahmet Kilic on the history of the neighborhood’s architecture; and design workshops by other local architects and designers on lighting, urban landscaping and color.

- On Saturday October 28th: A walking tour of McMillan Park, an historic landmark designed by Frederick Law Olmsted that surrounds the McMillan Park Reservoir. Led by local resident Paul Cerruti, the tour will highlight the park’s history, vistas and connection to Bloomingdale.

Preservation "saved" the city. I've argued for many years that combined with the urban design begat to the city by Pierre L'Enfant. and until recently both a robust transit system and the steady employment engine of the federal government, neighborhoods constructed of attractive historic architecture are a fundamental component of the city's "competitive advantage" and primary "unique selling proposition," for choosing to live in the city.

The Bloomingdale neighborhood is typical in that it features historic architecture but is not designated as historic, so buildings lack the protections present in other districts such as Capitol Hill.

The Bloomingdale neighborhood is typical in that it features historic architecture but is not designated as historic, so buildings lack the protections present in other districts such as Capitol Hill.During the many decades that residential choice trends disfavored center city living, people who found cities and historic architecture attractive moved in regardless, despite the evident problems with crime, poor quality schools, and dysfunctional municipal government.

Preservation provided a strategy and approach capable of stabilizing neighborhoods that otherwise were experiencing population loss and decline.

As trends reversed and favored a reconsideration of urban living, which became evident around 2000-2005, simultaneously the population of residents favoring the city finally hit critical mass, so that the momentum of neighborhood stabilization and improvement became self-sustaining.

Unfortunately, while the positive economic and stabilization impact of preservation on cities and urban revitalization is widely understood among professionals, that realization hasn't been accepted more widely, especially by elected officials (often influenced by real estate development interests) and other stakeholders.

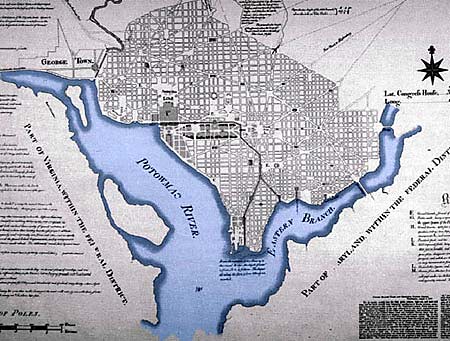

Interestingly, this is true despite the fact that DC is a classic example in urban planning as being a "designed" city through the creation of a master urban design plan for the city by Pierre L'Enfant.

Known as the L'Enfant Plan, it called for the creation of a grid system organized as blocks and streets, bisected with radial avenues, and at those locations where the avenues intersected with streets otherwise laid out at right angles, "circles" (called reservations), plazas and squares were to be created to showcase civic functions. The L'Enfant Plan and the city's urban design is a historically designated feature of the city.

Books such as The Living City and Cities: Back from the Edge by Roberta Gratz, and Changing Places by Richard Moe are particularly good resources on the value of historic preservation as a sustainable urban revitalization strategy as is Economics of Uniqueness: Investing in Historic City Cores and Cultural Heritage Assets for Sustainable Development, published by

How does the preservation movement grapple with growth? Today, increased demand to live in the city, especially in "historic" buildings, puts great pressure on neighborhoods, mostly in price appreciation, because it is not possible to produce more historic buildings ("Exogenous market forces impact DC's housing market," 2012), and because most sites suitable for single family housing have already been developed.

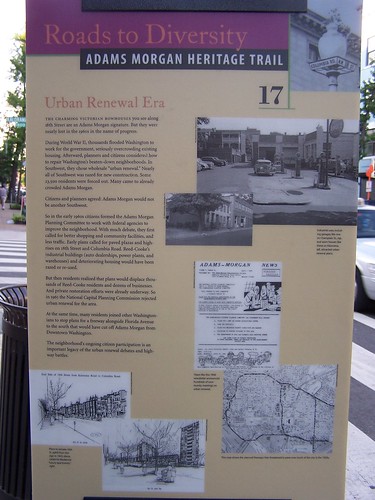

Preservationists developed their skill set when stabilization was the priority, simultaneous with the need to protect communities from unfriendly urban renewal and freeway initiatives and discordant architecture.

DC neighborhoods abutting the central business district also had to ward off the expansion and extension of the business district into residential quarters, because the height limit made it impossible to build taller in order to accommodate commercial demand (see the reprint of the 1974 Washington Post editorial, "Preservation Frustration," within this past blog entry). This further biased preservationists to reflexively oppose new projects.

DC neighborhoods abutting the central business district also had to ward off the expansion and extension of the business district into residential quarters, because the height limit made it impossible to build taller in order to accommodate commercial demand (see the reprint of the 1974 Washington Post editorial, "Preservation Frustration," within this past blog entry). This further biased preservationists to reflexively oppose new projects.But today, given 21st century circumstances and conditions, cities need more population and commercial activity in order to be economically resilient.

Mostly, because of the high cost of land, new housing tends to be multiunit, and is inserted somewhat surgically into neighborhoods through conversion of properties in commercial districts, on land in and around transit stations, and sometimes through the conversion of formerly institutional properties.

How do preservationists update their approach to help cities become stronger, more stable and resilient during growth conditions?, especially when economists like Edward Glaeser argue (see his book, Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier and Happier; review from The Economist) that preservation unduly limits growth

DC has the strongest historic preservation law in the US. By that I mean that (1) buildings can be nominated and designated without requiring owner permission; (2) decisions are made impartially by an independently appointed commission, the Historic Preservation Review Board; (3) unlike in other communities, neither the Executive Branch (Mayor) nor City Council (Legislative Branch) make the final decision and they lack the authority to overturn decisions; (4) for the most part, buildings that are listed, either as landmarks or as "contributing buildings" within historic districts can't be demolished; (5) changes are reviewed, and are required to be in keeping with the building's architectural style and period of historic significance.

The Kennedy-Warren Apartment Complex was constructed during the Depression. A loss of financing meant that part of the planned building was not constructed until the early 2000s.

The Kennedy-Warren Apartment Complex was constructed during the Depression. A loss of financing meant that part of the planned building was not constructed until the early 2000s.What separates DC's law from virtually every jurisdiction is that an impartial board makes the decisions and they can't be countermanded by politics--although that being said, some of the board members are definitely "political" appointees, not preservationists, and they may not always make decisions that are based on the architecture and history rather than politics.

Another element of preservation regulations that people sometimes may not grasp is that in a historic district, proposals to change properties, build new buildings, etc., require mandatory review, while in undesignated areas, the equivalent project can be "matter of right" and no extranormal review triggering citizen involvement is required.

Preservation regulations provide a framework and process for "managing change."

But the preservation law only protects properties and districts that are designated. DC's preservation law is great, but only covers those properties and districts that have already been designated.

DC has no demolition protections for buildings that would qualify to be listed as historic resources. There is only one remedy to protect an undesignated building, and that is to designate it.

This unusual feature of an oriel on the alley side of a rowhouse is located on the unit block of R Street NW in the undesignated Bloomingdale neighborhood.

But for that to work, the building must satisfy a high ceiling. The average building cannot meet that threshold. And there is no quick way to create a large historic district.

Note that the building regulations do provide for retaining particularly distinctive architectural features such as turrets in undesignated buildings, but a process for ensuring this happens is underdefined, as is the definition of what qualifies--porches?, oriels (above grade bay projections)? porches?, cornices?, etc.

The Columbia Heights rowhouse architecture tends to be larger than many other districts across the city. The neighborhood is undesignated. Washington Post photo.

The Columbia Heights rowhouse architecture tends to be larger than many other districts across the city. The neighborhood is undesignated. Washington Post photo.While arguably DC has more historic districts and protected properties than any other city in the U.S. (although New Orleans and New York City sometimes argue otherwise), the number of undesignated properties and districts eligible for designation is a much larger number.

An important question that few people ask is what strategies are there for protecting the buildings and districts that are unprotected?

In the last few decades a rise in property rights sentiments and changes to laws and regulations have made it much more difficult and cumbersome to create new historic districts compared to the time when areas like Capitol Hill, Anacostia, Dupont Circle, and LeDroit Park were designated.

(Although the process for landmarking individual buildings has not been affected by these changes.)

This is complicated by the fact that to many people, an "ordinary" house doesn't seem "historic" compared to Mount Vernon, the U.S. Capitol, or the Chrysler Building, even if it is more than 100 years old, "it's just an old house" (past blog entry "Historic preservation and public history: whose history is history anyway?," 2009).

Therefore it becomes much harder to protect buildings in "an average neighborhood," even if elsewhere the same building would be considered historic.

Housing demand puts pressure on extant buildings. As demand for housing in the city increases, and because most land zoned for single family housing has already been built upon, this puts pressure on extant housing in an urban "McMansionization" phenomenon, converting properties to flats/condominiums, constructing additions either outward or upward, and demolition and replacement with bigger buildings.

Although at the same time we have to acknowledge that larger buildings and lots may be better utilized if "expanded" to a set of smaller units, and can accommodate such changes somewhat easily with minimal negative impact on a neighborhood (depending on the nature and quality of the changes).

Discordant third floor addition on a corner rowhouse in Bloomingdale. Photo by Steve Pinkus.

Discordant third floor addition on a corner rowhouse in Bloomingdale. Photo by Steve Pinkus.Upward additions, referred to as "pop ups," create controversy because the new sections tend to be out of proportion and use different materials compared to when the buildings were originally constructed ("Changing matter of right zoning regulations for houses to conform to heights typical within neighborhoods, not the allowable maximum," 2012).

More recently, building regulations have been changed to make conversion more difficult, but haven't stopped such efforts altogether in undesignated areas, which lack the requirement for additional review that is mandated for historic districts.

No special protections for avenues. Another area where new protections are needed are the city's "avenues," streets like Massachusetts Avenue, Wisconsin Avenue, and Connecticut Avenue, but also streets without "avenue" in their name, like 16th Street, which tend to be lined by majestic apartment buildings and other distinctive buildings constructed mostly before the 1940s, but even into the 1960s most buildings constructed on such streets were designed with aesthetics in mind.

5333 Connecticut Avenue NW. WBJ photo.

Now aesthetics are of little concern and new buildings such as 5333 Connecticut Avenue NW ("After 25 years and a neighborhood kerfuffle, Cafritz readies 5333 Connecticut for tenants ," Washington Business Journal) generally are a poor fit ("An argument for the aesthetic quality of the ensemble: special design guidelines are required for DC's avenues," 2015) compared to extant apartment and condominium buildings from the past.

Best Addresses by James Goode, published by the Smithsonian Institution Press, discusses the architecture of DC's apartment houses.

But the point in the Rehabilitation Standards:

"Each property shall be recognized as a physical record of its time, place, and use. Changes that create a false sense of historical development, such as adding conjectural features or architectural elements from other buildings, shall not be undertaken"

generally has been interpreted to mean that new construction in historic districts should be of the current time, rather than a copy of the old.

In the field, there is a debate about this, whether architecture should be "of its time" or "of its place." One of the reason that the "of its place" argument is so important is that the inclusion of new construction of different design tends to cheapen the whole of a district, certainly of its block, as it tends to be out of character and it shows.

Of its place represents the position that the quality of the overall built form matters the most, when it comes to livability and maintaining the qualities that make neighborhoods great places.

I've been fortunate to hear Professor Steven Semes speak on this and he's also written about it, in "New Buildings Among Old: Historicism and the Search for an Architecture of Our Time" and more in depth in book form, The Future of the Past: A Conservation Ethic for Architecture, Urbanism, and Historic Preservation (review of the book from Traditional Building Magazine).

Semes' paper lays out all the arguments for why the way these issues have been interpreted lead to the "decontextualization of historic buildings—they become museum artifacts instead of remaining part of our living world." His concludes that:

This growing dissent within the architectural and preservation communities represents the paradigm shift now in progress as the grip of historicist doctrine is gradually broken. In its place, a new conservation ethic is emerging, drawing together traditional architecture, new urbanism and historic preservation in pursuit of a built environment that is beautiful, sustainable and just. In the new paradigm, the architecture of our time will be the result of a critical engagement with the architecture of place, seen as a continuously self-renewing field of character and civility.There are some good examples of new construction that fits in quite well, and other that doesn't. But the majority of new buildings don't work well, in terms of design, materials, and proportions.

Preservation as a manipulative tool/opportunity costs. One of the problems that arises from the existence of preservation regulations is that they can be manipulated as a way to fight development proposals, no matter how worthy.

Such practices lead many people to criticize historic preservation as a hindrance and barrier to "progress."

And because of the mandated review process, it is not uncommon for final approvals to include project shrinkage to assuage/as a sop to community concernings, without acknowledging the economic opportunity cost to the city in terms of fewer units leading to fewer residents, lower property, income, and sales tax revenues, and higher housing prices due to supply constraints.

Recommendations: mandatory design review. Recognizing that the city's competitive advantage is tied to historic architecture, I've argued for a long time that the city should mandate design review for new construction, whether or not an area or building is historically designated.

Other cities such as Baltimore and Cleveland have special design review requirements for certain types of projects, whether or not they are in historic districts. Lancaster, Pennsylvania does the same for the core of the city, which was built in the 1700s and 1800s.

Another way to think about this conceptually is DC at the scale of a cultural landscape, and to ensure that as a whole the city's aesthetic qualities are maintained and supported, create a design review process focused on creating better outcomes.

This colonial revival brick house on 9th Street NW near Piney Branch Road likely dates to the 1940s. The original construction was primarily brick. But a second floor addition was fitted with frame-style siding, which is a building material that is incongruent with the original construction and architectural style.

The idea wouldn't be to prevent new development, but to ensure that from a design standpoint, the new construction would be more compatible and architecturally proportionate.

For example, with popups and additions, new additions would have to be constructed with compatible materials.

DC's Historic Preservation Office publishes such guidelines for work in historic districts, including Additions to Historic Buildings and New Construction in Historic Districts.

But there is no requirement that these resources be consulted and followed in those areas of the city that are not designated as historic.

The city's Comprehensive Plan, Zoning Code, and set of building regulations should be revised to recognize this need and lay out guidance and a process for addressing and providing design review for those parts of the city that are not historically designated.

"Of its place" should be the guiding principle for new construction in residential neighborhoods, while such decisionmaking can be more flexible in commercial and transit districts, depending on the site, context, and the nature of the built environment around the site.

This aerial view of DC's Logan Circle (image from Wikipedia) shows how circles and avenues shape DC's cultural landscape and are a signature element of the urban design created by the L'Enfant Plan.

This aerial view of DC's Logan Circle (image from Wikipedia) shows how circles and avenues shape DC's cultural landscape and are a signature element of the urban design created by the L'Enfant Plan.Recommendations: mandatory design review for DC's avenues. The architectural coherence and attractiveness of the city's avenues should also be a priority.

While the Comprehensive Plan describes the city's avenues as an important element of the city's urban design, it makes no substantive recommendations with regard to maintaining, extending, and enhancing the architectural integrity and attractiveness of the city's avenues, which are key gateways into and out of the city.

The city's "circles" and the triangular lots that are formed where the grid of numbered and lettered streets intersect with the avenues provide special opportunities for particularly unique, interesting, and attractive buildings (see the past blog entry "16 Grant Circle and the landscape of DC's avenues and circles as an element of the city's identity").

Unfortunately, in today's era of modern and post-modern architecture typically these opportunities are ignored in ways that diminish the overall beauty of the city.

The city's Comprehensive Plan, Zoning Code, and set of building regulations should be revised to recognize this need and lay out guidance and a process for addressing and providing design review for those sections of avenues that are not designated.

"Of its place" should be the guiding preference for new construction on the city's avenues, for residential buildings definitely, and for commercial buildings preferably, depending on the site and its context.

Pattern books as a model for forward progress. Ideally, like in the days of pattern books ("History of the Pattern Book," City of Roanoke; "The Institution of Residential Investment in Seventeenth-Century London," Business History Review (Jstor]), more structured guidance could be provided to ensure that new construction "works," both for new buildings and with modifications for existing buildings.

More recently, pattern books have been a major component of work within the field of "New Urbanism," as a way to ensure design harmony within new developments as well as infill construction.

But many existing communities are creating pattern books as a way to provide more structured guidance, with the aim of facilitating development, simplifying the regulatory process, and ensuring higher quality outcomes from new construction.

As examples, the City of Roanoke published an award-winning Residential Pattern Book, and the City of Alexandria, Virginia has been developing a similar document for the Del Ray neighborhood.

Besides the Historic Preservation Office publications mentioned above, in the 1970s DC created similar publications for the Anacostia and LeDroit Park neighborhoods, and in 2014 a pattern book was created by the city's Department of Housing and Community Development to shape infill development for the Congress Heights and Anacostia neighborhoods.

DC should direct more resources to the development of pattern book type treatments specific to the rowhouse type and its various architectural variants such as Second Empire and the porch front variant of the Craftsman style.

Multiunit buildings. Best Addresses is a DC-specific resource, but other books and resources from other cities and other resources can also be compiled and codified to provide pattern book guidance for multiunit residential buildings.

Some resources include Apartment Buildings & Hotel/Motels Building Types produced by the Utah Division of State History, articles on Chicago building types, "The Residential Hotel," and "Courtyard Apartment Buildings," from the Moss Architecture blog. books, etc.

Because of the cost to repair, this unique two-story oriel on a building at the northwest corner of the intersection of 12th and H Streets NW was pardged and enclosed, significantly diminishing the architectural integrity of the feature, the building, the block, the intersection, and the street.

Conclusion. If resources aren't used, they are immaterial. As recommended above, there need to be requirements and processes put in place for design review across the city so that not only are resources consulted but the appropriate guidance is applied to construction projects going forward, with the aim of maintaining historic architecture and aesthetic attractiveness of the city's built environment as a fundamental element of the city's competitive advantages and "unique selling propositions" in the 21st century as much as this had been key to the city's competitive advantage from its founding in the 1790s through the early part of the 20th century.

Labels: building regulation, historic preservation, neighborhood revitalization, real estate development, urban design/placemaking, urban revitalization

7 Comments:

Hi, Richard. Very nice recap of issues and excellent links. Just one minor thing, "The Economics of Uniqueness" was published by the World Bank, not UNESCO. Keep up the good work.

Oopsy. Glad you're reading (if you are, then again, I don't write that much HP anymore, however, in Nov. with the Nat. Trust meeting I will do a review of Stephanie Meeks' book -- I haven't finished it yet, but it's definitely not the book I'd have written-- and a couple others, and lay out what I think are the big issues in urban preservation).

I will correct. Thanks for taking the time in pointing it out.

Design review would allow investment into area to densify them from say 2 stories to 4 stories while maintaining a coherent identity.

the Growth Machine is very different than the real estate interests that have saved historic areas.

I just added a photo to the section on design review of a popup at 3615 10th St. NW.

Yes, I can accept desires for additions, just want the aesthetic elements to be prioritized.

And yes, the Growth Machine pretty much is about intensification, and the value of land is only in the land available "for assembly," not encumbered by those pesky old houses.

Basically, I got my education in this living in the H Street neighborhood.

My joke is that my heightened interest in urban revitalization is merely "blowback in response to the activities of the H Street Community Development Corporation."

They had a very urban renewal approach to "improving the neighborhood." I argue that it didn't work, despite the expenditure of more than $100 million. (Hey, like Sandtown-Winchester.)

But its locational advantages -- proximity to Union Station, Capitol Hill, Downtown -- coupled with the historic building stock allowed it to overcome the misguided approach.

From 2005:

http://urbanplacesandspaces.blogspot.com/2005/07/falling-up-accountability-and-dc.html

Later stuff:

http://urbanplacesandspaces.blogspot.com/2013/03/the-community-development-approach-and.html

http://urbanplacesandspaces.blogspot.com/2013/05/360-apartment-building-giant.html

(among others).

That being said I understand the need/value of intensification. Just see the opportunity for a balanced approach.

e.g., in this post I didn't mention that I am in favor of revisiting the height limit, at two scales, Downtown (maybe as much as double the current height, or more) and "rest of the city" which should allow for bigger than now.

E.g., the Courts said that a 4-6 story building was too tall for Brookland (Col. Brooks matter), whereas I would define that as "moderate" density, they considered in "very dense."

Need more details on 'design review.'

What is the basis for review? What standards are being used? Stylistic ones? Substantive ones around use? Is the review administrative or something deeper (i.e. the zoning commission)? Does a project require approval before advancing?

Basically, the complaint against a project like 5333 CT Ave seems illustrative - what kind of actual design review procedure would produce a 'better' outcome?

Broadly speaking, it's important that we have by-right development authority here, and reducing that legal entitlement could have tremendous consequences of slowing things down, adding tremendous cost. The benefits of design review would have to be large.

I don't follow Charlie's suggestion that design review could allow for 2 story buildings to become 4 story ones. On what legal basis? On what political basis?

Note that we do have design review in several non-historic areas. The Capital Gateway overlay zone around the Ballpark is one.

read Semes and apply context sensitive design principles.

I understand the point about increasing costs. It's a balance, but at the same time, the way that the buildings fit in (or not) lasts for decades. More time upfront has long term payoff.

Besides how HPRB and other design review procedures work, urban design review procedures in Cleveland and Baltimore are another model. Same with the "business revitalization district overlay" in Cleveland too.

It's not that developers are unable to do a better job, it's that MOR doesn't incentivize them to do so.

But the way I think of the process would be to (1) treat DC as a whole as a kind of "heritage area"

(2) do a basic evaluation of each district in terms of its era of architectural significance, lay out the basic building types common to the time, along with the predominate architectural styles

(3) promote design within that context, although in some situations, perhaps "new" design of its time may be acceptable.

With 5333 there should be general urban design guidelines for Connecticut Avenue by sub-zone and the design for 5333 should have been shaped accordingly.

Probably way more art deco, judging by the similar buildings in the vicinity, when they were built, and their architectural styles.

A couple more examples would be the JBG building on the 1300 block of U vs. the Martin Jawer building on the 1200 block of U, and the Donatelli building across the street (Ellington) and on 14th Street, the Donatelli building at Petworth, the Donatelli buildings at Columbia Heights, the Senate Square buildings on H Street, 360 H Street, the new Hine complex at 8th and Pennsylvania SE (which I will be writing about), etc.

Basically, developers who hold properties tend to invest more in aesthetics than those who don't.

Post a Comment

<< Home